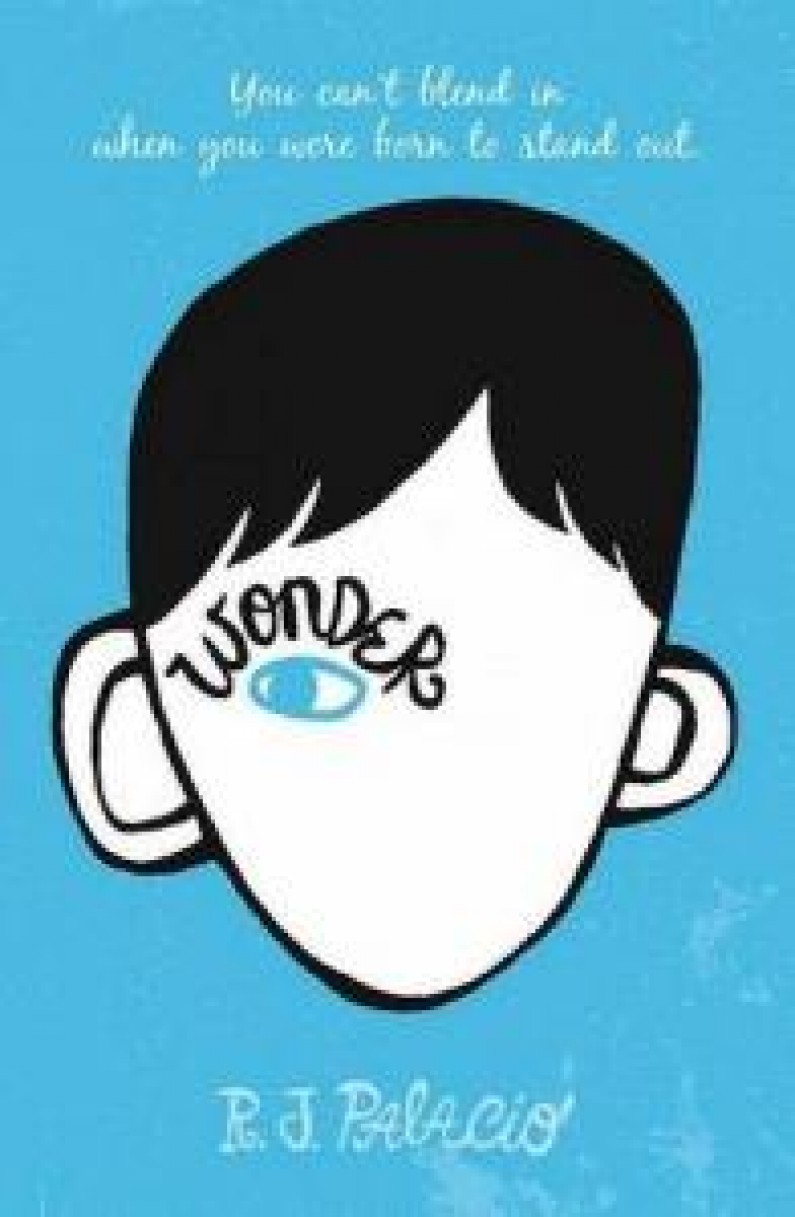

Children's books become a healing tool

Book-jacket designer Raquel Jaramillo never intended her first book to take a stand against school-yard bullying.

Wonder is the fictional story of August Pullman, a fifth grader born with a chromosomal abnormality that disfigures his face.

From Australia, New Zealand, Britain and the tiniest corners of rural United States, Jaramillo, writing under the pen name R.J. Palacio, has received thousands of letters and emails from children saying Wonder has made them want to be better people.

"That's amazing to hear from 10-year-olds," says the New York-based writer, whose book has been revised to include the bully's perspective.

There is now an entire shelf of children's and young adults' fiction that model difference and tolerance. It's not just bullying. Cancer, depression, autism, gender confusion and learning difficulties are making their way into children's books.

Teachers, parents and librarians have picked up these books-with-a-cause as a reading resource to help children and teens rehearse ways they can confront taunts, social exclusion and violence. And they have turned them into unexpected best sellers.

Wonder has sold more than a million copies worldwide, 33,000 copies in Australia. John Green's The Fault in our Stars, a romance about teens with cancer, has notched up 10 million sales worldwide.

Anti-bullying campaigner Susanne Gervay is certain a literature-based approach can break down stereotypes and save lives.

Gervay is the creator of the I am Jack series. She describes her books as part survival manual, part fiction, which distil issues of difference, tolerance and anxiety into digestible bits by which young readers can reach some understanding of their problems.

Too often children are given too much credit for being able to communicate their feelings, says Gervay.

"I go into schools and children tell me their stories," she says. "When I hear a 12-year-old ask, 'what is the point of life?', I want to hug them and tell them it's going to be alright. I had one girl who muttered under her breath, 'I want to die', and, you know, I took her by her hand and brought her friends around her and made them vow that they would be there for this girl whenever she felt lonely or upset."

The value of literature as a therapy tool has long been recognised by the Australian Association of Family Therapy which this time every year honours books that help children deal with divorce, disability and other difficulties.

This year's winner in the young adult category is Aimee Said's Freia Lockhart's Summer of Awful, about a girl who must cope with her mother's diagnosis with breast cancer. It was selected for its realistic setting, strong role models and positive outcomes.

One of last year's winners, I'll Tell You Mine by Pip Harry, shows how parents deal with their teenage daughter's difficult behaviour while the other, Violet Mackerel's Personal Space by Anna Branford, was praised for its positive depictions of step-parenting.

Linda Stock, a member of the book awards' panel for nine years, has studied the benefits of reading for children who have spent long periods in hospital and uses Going Home by Margaret Wild and Wayne Harris as her text.

While she was reading to young patients in Royal North Shore Hospital, one boy told her books helped him "get out of his hospital bed and into his imagination".

Stock says she avoids books that are glib or contain glaring stereotypes and likes Pip's Magic by Ellen Stoll Walsh, which is about dealing with fear but is code for the message "we have the skills we need, and are already brave".

The spoken-word artist Shane Koyczan is the latest writer to put his own pain into print. His anti-bullying poem To This Day describes the life-long repercussions of school-yard bullying. Koyczan was the fat kid at school and has been haunted by taunts of pork chop. His message is: names do hurt but, if you can't find beauty in yourself, "find a better mirror".

Books that use humour, provide hope and offer a positive outcome are most helpful as a teaching tool. But the story must have integrity, says Jaramillo.

"Kids eyes' glaze over a bit nowadays when they're told in any kind of didactic manner, don't be a bully. Very few kids see themselves as bullies. They don't identify what they're doing with bullying if it doesn't fit into the cliches of bullying.

"They don't see how socially isolating someone is a form of bullying. They don't recognise themselves in that label. And neither do their parents."

Linda Morris Sydney Morning Herald Article